About Us

Solutions

What a subsidiary is, how it differs from affiliates and divisions and why businesses use subsidiaries for strategy, expansion, and more.

What a subsidiary is, how it differs from affiliates and divisions and why businesses use subsidiaries for strategy, expansion, and more.

Your lawyer just casually mentioned setting up a "subsidiary structure" for your expansion into a new state.

Your accountant is talking about "consolidated reporting" for your new entities.

Your business partner wants to know if spinning off the high-risk division into a separate company makes sense.

You nod along professionally while secretly wondering: What exactly is a subsidiary, and why does everyone seem to think I need one?

Welcome to the world of corporate structures, where subsidiaries aren't just complex terms they can take on functions that can shield your assets, help you pay less in taxes, and even help you grow your company.

What most CEOs think of their subsidiaries in terms of is insurance policies—something other companies own that might come in handy someday.

However, enhanced businesses utilize subs in terms of being tools of empowerment in market expansion and risk management tactics.

The understanding of the workings of subsidiaries goes beyond corporate complexities—it involves the mobility of strategy to secure what you've achieved while preparing for what the next stage brings.

A subsidiary company is one that is controlled by another company, known as the parent company.

The subsidiaries exercise independent operations, while they remain subject to the control of the parent companies in terms of strategies and finances.

Subsidiary company: The subordinate company whose control vests in another company because it owns a controlling stake, mostly in excess of 50% of voting stock.

The ownership threshold accorded to the parent company confers upon it control over the operation of the subsidiary, the appointment of the board of directors, and major policy-making decisions.

The legal position is very simple:

The parent firm has voting shares sufficient to control the operations of the subsidiary, yet it retains the separate identity of the latter.

This allows the subsidiary to enter into contracts, own property, assume liabilities, and carry out business in its own name and under its own laws.

Ownership thresholds are far more significant than you might think.

You exercise control because you own 50.1% of it directly, and you can make unilateral decisions with regard to the operation of the subsidiary company.

Despite being completely owned, subsidiaries are separate entities with balance sheets, earnings centers, and management duties. Such separateness gives rise to opportunities and challenges that only astute CFOs can capitalize on.

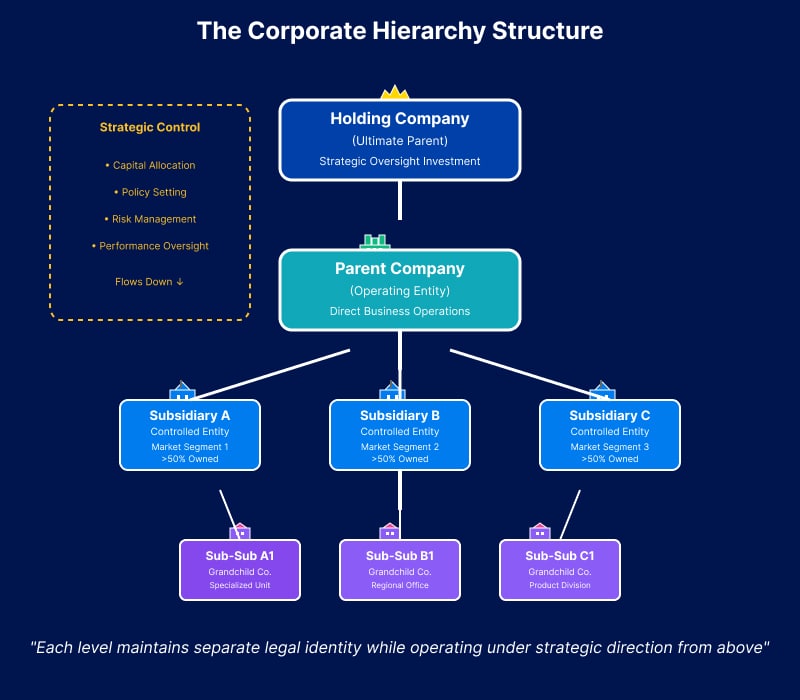

The parent-subsidiary relationship creates a corporate hierarchy where strategic control and operational responsibility are carefully distributed across separate legal entities.

This hierarchy becomes especially significant while working with ultimate vs immediate parent companies.

The subsidiary can be directly owned by one company, referred to as the immediate parent company, while being ultimately controlled by the large corporate body referred to as the ultimate parent company.

Think of how Instagram is immediately owned by Meta, but if Meta were owned by another company, that would become Instagram's ultimate parent (Kind of Like Instagram's "Grandparent")

The distinction matters for regulatory compliance, tax planning, and understanding the true decision-making authority within complex corporate structures.

Subsidiary structures aren't one-size-fits-all—the level of ownership determines strategic flexibility, financial control, and operational complexity.

A wholly owned subsidiary provides maximum strategic control and operational flexibility. The parent company owns all voting shares and can make unilateral decisions about operations, financing, and strategic direction without consulting minority shareholders.

The partially owned subsidiaries hold controlling stakes while being accommodating to minority shareholders.

Such an arrangement might arise from joint ventures, acquisition tactics, or even where local players hold advantageous knowledge of the market or regulations.

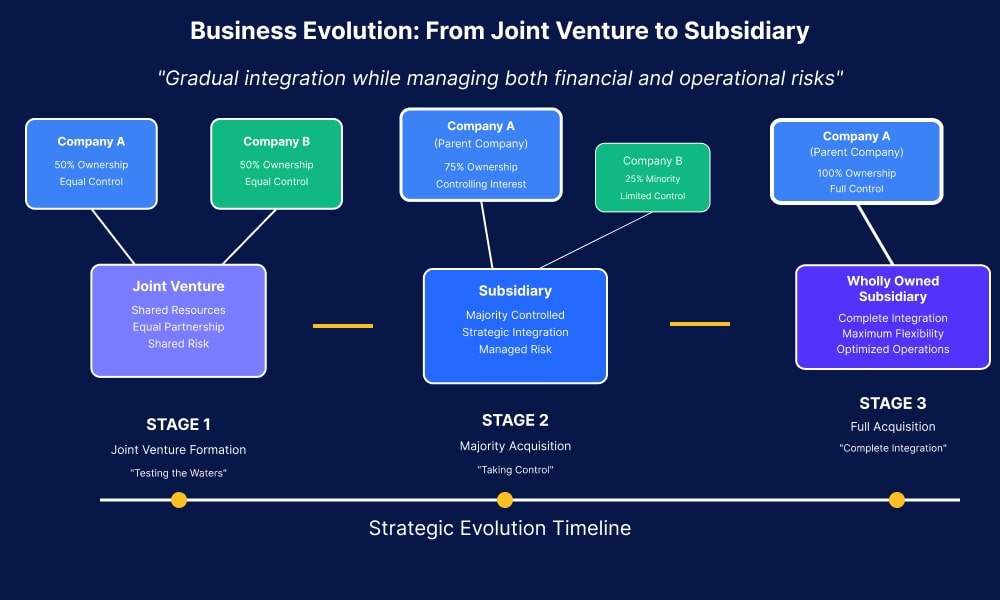

Many corporations begin with joint ventures that develop into subsidiaries as the arrangement matures and goals are defined.

This allows for phased integration while controlling risks in terms of finances and operations.

Subsidiary structures aren't created for accounting complexity—they're strategic tools that address real business challenges and opportunities.

These subsidiary structures are not designed to deal with accounting complexities but rather serve as tools to counter real-world challenges and opportunities in businesses.

They Limit Legal and Financial Liability

Subsidiaries offer protection to the assets of the parent company against risks associated with the subsidiaries. For instance, if there are any lawsuits, fines, or difficulties in the subsidiary, the only effect on the parent company is the amount it has invested in it.

Such protection becomes essential for corporations involved in high-risk sectors and fluctuating markets. An organized method for risk management in subsidiaries can help segregate risks while ensuring control over operations and strategies.

While expansion on the geographic and industry level may necessitate the use of subsidiary structures to deal with local regulations and market requirements, these subsidiaries can help companies maintain control while being incorporated locally.

International subsidiaries address currency risks, regulatory compliance, and tax optimization opportunities that wouldn't be available through direct operations. This becomes particularly important for companies expanding into markets with complex regulatory environments or unique operational requirements.

Companies often establish subsidiaries to isolate operations that could pose financial or reputational risks to the main business. This separation allows for aggressive growth strategies in new areas while protecting established revenue streams and stakeholder relationships.

Such cases might include technology companies establishing subsidiaries for new product development, manufacturing companies that separate research and development units, or services companies that separate units with high operational risk.

Subsidiary corporations facilitate complex branding and intellectual property tactics that would not be feasible in single-entity businesses.

Companies can develop distinct market identities, protect valuable IP assets, and optimize licensing arrangements across different business units and geographic markets.

This becomes particularly valuable for companies with diverse product lines or services that target different customer segments or market conditions.

Understanding corporate hierarchies helps clarify how subsidiaries relate to other business structures and why CFOs choose specific organizational approaches.

This hierarchy enables sophisticated capital structure decisions and operational flexibility while maintaining centralized financial control and strategic oversight.

Holding Companies own subsidiaries as investments, but typically don't engage in direct operational activities. They exist primarily to hold and manage subsidiary investments.

Divisions are internal organizational units that aren't separate legal entities. They provide operational organization but don't create legal separation or liability protection.

Affiliates represent relationships where ownership exists but doesn't constitute control (typically less than 50% ownership). These relationships provide influence but not operational control.

Affiliate investments provide market access and strategic influence without full operational responsibility. They're useful for entering new markets, accessing technology or expertise, and building strategic partnerships that may evolve into acquisitions.

Subsidiaries provide liability protection and operational flexibility but require separate legal compliance, financial reporting, and governance structures. They're ideal for high-risk operations, geographic expansion, and distinct business models that benefit from separate legal identity.

Understanding how major corporations use subsidiary structures provides insight into strategic applications and best practices.

Google LLC operates as Alphabet's primary subsidiary, handling search, advertising, and core technology operations. YouTube LLC functions as a separate subsidiary, maintaining a distinct operational identity while benefiting from Alphabet's resources and strategic direction.

Waymo LLC (autonomous vehicles) and Verily Life Sciences LLC (healthcare technology) operate as distinct subsidiaries, allowing Alphabet to pursue high-risk, high-reward opportunities without impacting core search and advertising

This structure enables Alphabet to report segment performance, allocate capital efficiently, and maintain strategic flexibility across diverse technology investments.

Instagram LLC and WhatsApp LLC operate as Meta subsidiaries, maintaining their original brand identities while integrating with Meta's broader advertising and technology platforms. This approach preserved user loyalty during acquisition while enabling strategic integration and resource sharing.

The subsidiary structure allows Meta to optimize advertising capabilities across platforms while maintaining distinct user experiences and brand positioning.

This separation becomes critical when parent company decisions clash with subsidiary brand identity.

In January 2025, Instagram's shift from square to portrait grid tiles triggered a bit of user backlash as legacy posts were cropped and artistic compositions destroyed. The subsidiary structure allowed Instagram to absorb this brand-specific issue without damaging Meta's broader ecosystem—demonstrating how corporate separation contains risks that could otherwise cascade across an entire portfolio.

The company, Amazon Web Services (AWS), functions in the manner of an independent subsidiary that allows it to demonstrate separate finances, thereby providing visibility to the extraordinary profitability and performance of the cloud division.

The current structure of the subsidiaries makes it possible for Amazon to efficiently oversee different models of doing business: retail businesses with low margins and cloud businesses with high profitability ratios.

Subsidiary structures create complex financial reporting requirements that CFOs must navigate to maintain compliance and provide stakeholder transparency.

Subsidiaries require consolidated financial statements that combine parent and subsidiary operations while eliminating intercompany transactions. Balance sheets are combined, with intercompany transactions eliminated to prevent double-counting. This creates a comprehensive view of the corporate family's financial position.

When subsidiaries aren't wholly owned, minority shareholders' interests must be reported separately in consolidated statements. This non-controlling interest represents the portion of subsidiary net assets and earnings that belong to minority shareholders.

CFOs must carefully track and report these interests to ensure accurate representation of parent company versus minority shareholder claims on subsidiary performance and assets.

Subsidiary structures offer tax optimization opportunities related to income allocation, transfer pricing, and selecting different jurisdictions. These must be considered in sophisticated compliance management processes.

When it involves the prices between the parent company and the subsidiary companies, it has to be arm's length in order to comply with the taxing authority and avoid being penalized.

Here's the truth about subsidiary structures that most business owners learn the hard way:

You're not just playing with legal entities. You're building the financial DNA of your company's future.

Growing companies that tried to DIY their corporate structures often discover they've created compliance nightmares, tax inefficiencies, or operational bottlenecks that cost more to fix than they would have cost to do right the first time.

If you're going through changes, mergers, or questioning whether your current structure supports your growth trajectory, CFO-level expertise isn't a luxury—it's survival insurance.

The companies that thrive during transitions don't just have great products or services. They have financial leadership that understands how to structure entities, optimize reporting, and navigate the regulatory complexities that can make or break expansion plans.

Whether you need interim CFO guidance during transitions, M&A expertise for complex transactions, or executive coaching to level up your financial leadership, the question isn't whether you need strategic finance expertise. The question is whether you get it before or after you've already made expensive mistakes.

Ready to optimize your corporate structure for growth, risk management, and strategic flexibility?

McCracken Alliance helps growing companies design and implement subsidiary structures that support expansion while protecting valuable assets.

Our fractional CFO network brings enterprise-level expertise to help you navigate complex corporate structures without the full-time commitment.

We're the strategic finance expertise you need to build corporate structures that enable growth while managing risk effectively.

Let's schedule your complimentary Corporate Structure Assessment today!

A subsidiary is a company that is controlled by another company, known as the parent, usually through ownership of more than 50% of its voting stock. The subsidiary operates as a separate legal entity while under the parent company's strategic control.

Yes. A wholly owned subsidiary is entirely owned by the parent company, providing maximum operational control and strategic flexibility while still functioning as a separate legal entity with its own rights and obligations.

Subsidiaries allow companies to manage risk by isolating liability, expand into new markets with appropriate legal structures, optimize tax strategies, and organize operations efficiently while maintaining centralized strategic control.

A subsidiary is majority-owned and controlled by the parent company (>50% ownership), while an affiliate involves less than 50% ownership, providing influence but not operational control over business decisions.

Yes. Subsidiaries are independent legal entities that can enter contracts, own assets, incur liabilities, and conduct business operations, even when wholly owned by another company. This legal separation provides liability protection for the parent company.