About Us

Solutions

What is fair market value and why does it matter? Explore the definition, key differences from book and market value.

What is fair market value and why does it matter? Explore the definition, key differences from book and market value.

You're reviewing a client's estate planning documents when their attorney mentions the family business needs a fair market value appraisal for tax purposes.

The business owner looks confused: "Isn't that just what I think it's worth?"

Here's what hundreds of business leaders discover every year:

Fair Market Value isn't about personal opinions or wishful thinking—it's a precise financial concept that drives everything from tax compliance to M&A negotiations to executive compensation.

Fair market value represents the price an asset would sell for on the open market between a willing buyer and a willing seller, both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts and neither being under compulsion to buy or sell.

Most executives encounter fair market value requirements without fully understanding how it differs from book value, market value, or their own internal valuations.

They either oversimplify the calculation or get overwhelmed by appraisal complexity, leading to compliance issues, missed strategic opportunities, and costly mistakes in business transactions.

This guide cuts through the confusion to show you exactly how fair market value works, when different calculation methods apply, and why sophisticated finance leaders treat it as a cornerstone of strategic decision-making.

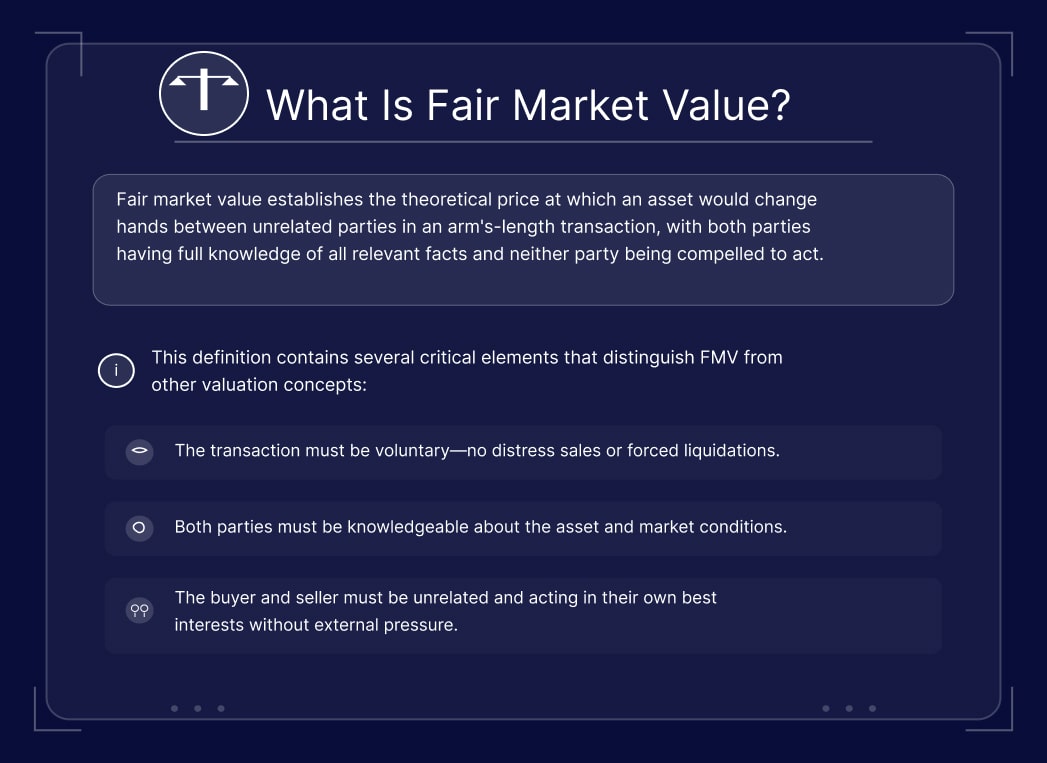

Fair market value establishes the theoretical price at which an asset would change hands between unrelated parties in an arm's-length transaction, with both parties having full knowledge of all relevant facts and neither party being compelled to act.

This definition contains several critical elements that distinguish FMV from other valuation concepts.

A fair market value determination may be required for purposes of calculating the estate tax due, for the reporting of gifts, or for claiming a charitable contribution deduction.

Valuing property below its true value may give rise to penalties, together with interest. Valuing in excess of true value may give rise to overpayment of taxes.

Fair market value serves as a baseline for M&A negotiations, helping establish whether proposed transaction prices reflect reasonable valuations or represent premiums and discounts to market conditions.

Under GAAP and IFRS standards, companies must report certain assets and liabilities at fair value, particularly financial instruments, impaired assets, and business combinations.

When granting stock options or restricted shares, companies need fair market value determinations to comply with tax regulations and establish appropriate exercise prices or grant-date valuations.

Fair market value provides the foundation for insurance claim settlements, property damage assessments, and litigation involving asset valuations.

Several interconnected factors influence fair market value calculations, and understanding these drivers helps executives make more informed valuation decisions.

Supply and demand dynamics in relevant markets directly impact fair market value.

For publicly traded securities, active trading provides continuous price discovery.

For private businesses or unique assets, market conditions require analysis of comparable transactions, industry multiples, and economic trends affecting similar assets.

The specific attributes of an asset—location, age, condition, income-generating capacity, growth prospects, and marketability—all influence fair market value.

A well-maintained manufacturing facility in a growing market commands higher values than similar assets in declining regions or poor condition.

Changes in tax policy, regulatory requirements, or industry-specific rules can materially affect fair market value. For example, recent tariff implementations have impacted valuations for companies with significant international supply chain exposure.

Assets with ready markets and high liquidity typically command fair market values closer to current trading prices. Illiquid assets or those with limited market access often trade at discounts to reflect the difficulty and cost of finding buyers.

Understanding the distinctions between these three valuation concepts prevents costly confusion in business transactions and financial reporting.

Growing Technology Companies:

A software company might have minimal book value due to intangible assets being expensed rather than capitalized, while fair market value reflects the company's growth prospects and competitive position.

Market value might exceed both if investor sentiment drives valuations beyond fundamental metrics.

Real Estate Holdings:

Commercial property book value reflects historical purchase price minus depreciation, while fair market value considers current rental rates, cap rates, and market conditions.

Market value represents actual transaction prices for similar properties.

Distressed Situations:

During corporate debt restructuring, book value might exceed both fair market value and market value if assets must be sold under time pressure or economic distress.

Fair market value calculation requires selecting appropriate methodologies based on asset type, available data, and intended use of the valuation.

This approach examines recent transactions involving similar assets to establish fair market value benchmarks.

For real estate, this means analyzing comparable property sales adjusted for differences in size, location, condition, and timing.

For business valuations, it involves studying recent acquisitions of similar companies and applying relevant multiples to the subject company's financial metrics.

For Example:

A manufacturing company seeking fair market value might examine recent sales of similar manufacturers, adjusting for differences in revenue size, profit margins, growth rates, and market position.

If comparable companies sold for 8-12 times EBITDA, the subject company's fair market value would fall within a similar range after appropriate adjustments.

DCF valuation projects future cash flows and discounts them to present value using an appropriate discount rate.

This method works particularly well for income-producing assets or businesses with predictable cash flow patterns.

The DCF approach requires careful consideration of growth assumptions, terminal value calculations, and discount rate selection using methods like WACC or risk-adjusted required returns.

This method calculates fair market value by estimating the current market value of individual assets minus liabilities.

It works well for asset-heavy businesses, holding companies, or situations where assets can be valued separately from ongoing operations.

Asset-based valuations require careful consideration of replacement costs, market values for used equipment, real estate appraisals, and the treatment of intangible assets like customer relationships or intellectual property.

The IRS provides specific guidance for fair market value determinations in various contexts, particularly for estate and gift tax purposes.

Revenue Ruling 59-60 establishes eight factors for valuing closely held business interests, including earnings capacity, dividend-paying capacity, goodwill value, market price of similar companies, and the company's financial condition.

Most business owners encounter IRS fair market value requirements reactively—when they need estate planning, face gift tax issues, or deal with equity compensation questions.

It’s smart to get ahead of these situations by understanding valuation principles before they need formal appraisals.

Fair market value calculations drive critical business decisions across multiple functional areas, making this more than just an academic exercise.

When business owners transfer company interests to family members or charitable organizations, the IRS requires fair market value determinations for tax reporting.

Undervaluing assets can trigger penalties and additional taxes; overvaluing wastes tax exemptions and creates unnecessary current tax obligations.

Family business owners often use fair market value appraisals to optimize succession planning strategies, timing transfers to take advantage of valuation discounts during periods of lower business performance or higher market uncertainty.

M&A transactions require fair market value assessments for individual assets, business units, and entire companies.

These valuations help establish negotiation ranges, identify synergies, and support fairness opinions for shareholders.

Acquirers use fair market value analysis to evaluate whether proposed purchase prices represent reasonable valuations or require justification through strategic premiums. Target companies use similar analysis to assess whether offers reflect full value or warrant negotiation for higher prices.

Companies granting stock options to employees must establish exercise prices at fair market value to comply with tax regulations.

Private companies need regular fair market value determinations for option pricing, while public companies can rely on market prices for most purposes.

Private company option pricing requires sophisticated valuation analysis considering marketability discounts, liquidity constraints, and the specific rights and restrictions associated with employee shares.

Insurance settlements for business interruption, property damage, or key person life insurance often require fair market value determinations.

Similarly, litigation involving business valuations, shareholder disputes, or economic damages relies on expert fair market value analysis.

Financial reporting and tax compliance create ongoing fair market value requirements that affect most businesses in some capacity.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) ASC 820 establishes the framework for fair value measurements in financial reporting.

Companies must measure certain assets and liabilities at fair value and provide detailed disclosures about valuation methodologies and assumptions.

Fair value accounting affects marketable securities, derivatives, impaired assets, and business combinations.

Companies must classify fair value measurements into three levels based on input observability:

The IRS scrutinizes fair market value determinations, particularly in estate and gift tax contexts where undervaluation can reduce tax obligations.

Common areas of examination include family limited partnerships, charitable remainder trusts, and employee stock option plans.

Taxpayers need well-supported valuations with appropriate documentation to withstand potential challenges.

Even experienced business professionals make costly assumptions about fair market value that can lead to compliance problems or missed opportunities.

The Misconception: Fair market value represents what assets would bring in a quick sale or liquidation scenario.

The Reality: Fair market value assumes reasonable marketing time and willing participants, not distressed or forced sales. Liquidation values typically fall well below fair market value due to time constraints and limited buyer pools.

The Misconception: For public companies, current stock prices represent fair market value for all purposes.

The Reality: Stock prices can be influenced by market sentiment, liquidity conditions, and short-term factors that don't reflect underlying economic value.

Additionally, minority interests in public companies might trade at discounts to pro-rata values of the entire enterprise.

The Misconception: Since private companies don't have public market prices, fair market value determinations are essentially opinions without objective support.

The Reality: Private company valuations rely on systematic methodologies, market data, and financial analysis. While judgment is required, professional appraisers follow established standards and use comparable market evidence to support their conclusions.

The Misconception: Selecting the "best" valuation approach provides the definitive fair market value answer.

The Reality: Professional valuations typically employ multiple approaches and reconcile the results to establish fair market value ranges. Different methods provide different perspectives on value, and the weight given to each depends on the specific circumstances and available data.

Companies that master fair market value thinking don't just avoid compliance problems—they position themselves to thrive.

They know when acquisition opportunities represent genuine value creation versus market hype.

They structure employee compensation programs that align incentives without creating unnecessary tax complications. They approach succession planning with realistic expectations rather than wishful thinking.

But here's what really matters: they sleep better at night knowing their major financial decisions are grounded in objective market reality, not just internal assumptions or optimistic projections.

The companies we work with typically hit three major roadblocks:

The Timing Challenge:

You need valuations when transactions are imminent, but quality appraisals take time and good ones require advance planning. By the time you realize you need professional help, you're working under time pressure that limits your options.

The Methodology Maze:

You know different assets require different approaches, but you're not sure which methods apply to your situation. Should you use comparable sales, DCF analysis, or asset-based approaches? The wrong choice can produce wildly different results.

The Professional Judgment Gap: Even with good data and appropriate methods, translating valuation results into strategic decisions requires experience most internal teams simply haven't had the chance to develop across multiple situations and market cycles.

Take succession planning, for example.

Some business owners might spend months perfecting their valuation models while missing the optimal timing for tax-efficient transfers.

Others were able to move forward quickly, sometimes due to the addition of structured interim CFO support during favorable market conditions.

Or consider an acquisition strategy.

The smartest buyers don't try to become valuation experts themselves.

Instead, they build relationships with experienced financial leaders—sometimes through fractional CFO partnerships, other times through targeted engagements—who can quickly separate genuine opportunities from expensive distractions.

Companies that treat valuation as an ongoing strategic capability rather than a one-time compliance exercise consistently outperform their peers.

They make faster decisions, avoid costly mistakes, and sleep better knowing their major moves are grounded in market reality.

Sometimes this means bringing in M&A consulting for a specific transaction.

Other times, it's about building your team's financial capabilities through targeted training so they can handle routine valuation decisions with confidence.

Want to see how this approach could work for your specific situation?

Every business faces different valuation challenges, but the conversation always starts with understanding your immediate priorities and long-term goals.

Whether you need help navigating a current transaction or want a strategic sounding board for major decisions, let's discuss how we can help you turn valuation complexity into competitive advantage.