About Us

Solutions

What corporate structure is, explore the most common types, and learn how it shapes governance, ownership, and strategic decision-making.

What corporate structure is, explore the most common types, and learn how it shapes governance, ownership, and strategic decision-making.

The first thing every executive must keep in mind about the structure of their organization?

The structure of the corporation extends beyond mere legal requirements and HR considerations.

Company organization is a strategic weapon that affects your scalability, innovation, and reaction to changes directly.

Do it right, and you have created something that makes all positive choices even better and prevents all poor decisions from becoming disasters.

One wrong move, and it's like playing telephone except the stakes are millions instead of incentives.

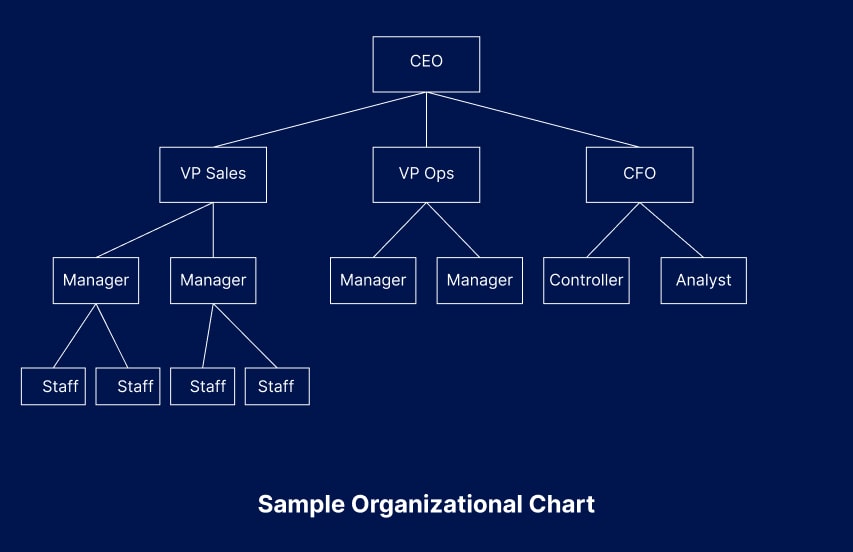

Corporate Structure: the framework created to determine how ownership, control, and operating functions interrelate in your business. This specifies who makes what decisions and who reports to whom, from corporate down to all other business levels.

It's not just lines and boxes on an org chart; it's the invisible architecture that makes all the difference between your firm running like a Formula 1 racing machine versus a bumper car from the county fair.

The ideal corporate structures provide clarity in three key areas:

They make sure that when "opportunity knocks," somebody actually has the power to answer the door and fix things if things go wrong, instead of just finding fault and creating a study committee to figure out what to do.

Read on to see if your corporate structure is working for you, or against you, and how to best optimize it.

The majority of firms typically fit into one of four basic structural configurations. These models have their advantages and challenges.

The trick is to align your architecture to your business strategy/size/growth stage—and not to emulate what you did last time or what looks good in some case study.

For example, marketing, finance, operations, and technology.

This structure truly is efficient, logical, and really perfect for companies where deep specialization matters more the cross-functional agility.

For example, in manufacturing companies, professional service firms, and early-stage businesses where expertise is more important than coordination.

Flips the script by organizing around products, markets, or geographic regions.

Each division operates almost like its own company, complete with dedicated functions and P&L responsibility. This model shines for companies with diverse product lines or global operations where local market knowledge trumps centralized efficiency.

Attempts to have it both ways by creating dual reporting relationships.Employees report to both a functional manager and a project or product manager.

It sounds elegant in theory and works beautifully for companies that need both deep expertise and cross-functional collaboration—think consulting firms, aerospace manufacturers, or large technology companies managing multiple product lines.

Minimizes management layers, pushing decision-making down to the people closest to customers and operations.

Startups and creative agencies love flat structures because they maximize speed and minimize bureaucracy. They foster innovation, employee engagement, and rapid response to market changes.

But flat structures hit natural limits around 150 people—the famous Dunbar number. Beyond that, coordination becomes chaos, and the lack of a clear management structure can actually slow decision-making as consensus-building replaces leadership.

A good org chart strikes a balance between span of control and depth of hierarchy. And research shows time and again that what works best for managers' span of control is to be responsible for anywhere from five to nine direct reports. Fewer direct reports result in unnecessary layers; more direct reports result in bottlenecks and weakened management

The visual elements have far greater significance than most executives appreciate. Clearly defined reporting structures, standardized naming conventions, and rational grouping systems can all help to clarify things for workers to ensure they fit into the larger context. When org charts resemble works of modern art or resemble genealogies from ancient mythologies, something is seriously wrong.

Startup Stage (5-50 employees): Flat structures involving direct reporting to the CEO. Emphasis here is on clarity of role rather than role hierarchy. Budget planning becomes critical even in this stage to facilitate structural development.

Growth Stage (50-200 employees): Establishment of management layers and departments. Span of control now must be defined. Often, it’s at this stage that organizations require part-time CFO help to set up scalable financial structures.

Mature Stage (200+ employees): Hierarchy structures have multiple management levels. Requires sophisticated financial planning and analysis tools to deal with increased complexity in organizational structures.

Smart organizations update their organizational charts quarterly and leverage them as tools for strategic planning, succession planning, and development opportunities. They’re not static charts sitting inside HR files but living charts aligned to evolving business needs.

A good org chart provides key information about span of control and reporting structures, and points to areas where control-level management may be required, and financial management duties can be allocated to different areas of the business.

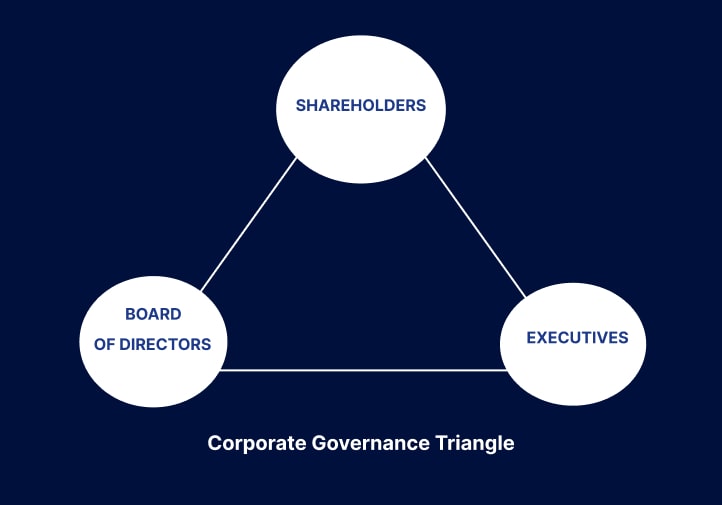

It’s here, where things start to get quite interesting for financial officers and business leaders in general. It all revolves around the complex interplay between ownership of the business, control of business operations, and management of both.

Shareholders own the company but typically don't run it day-to-day. They elect the board of directors and approve major decisions like mergers, acquisitions, or significant capital investments. In private companies, ownership might be concentrated among founders, employees, or private equity firms. In public companies, ownership is dispersed among thousands or millions of shareholders.

The executives direct their daily business activities based on strategies sanctioned by their boards. The CEO holds the highest level in such a corporate grouping structure, followed by other executives like the CFO, who deal with particular business functions. In this way, ownership and control issues occur in capitalism and result in endless complexities.

The Board of Directors bridges the gap between owners and managers by offering supervision and strategic inputs and is independent from management. A good Board must have industry knowledge combined with independent thinking to ensure accountability, but not micromanage.

The governance triangle impacts your organizational structure in very fundamental ways.

The composition and style of your board of directors will determine if you have centralized versus decentralized decision-making models, while your executive management team's preferences will determine if your reporting structures resemble functions, divisions, or matrices.

The importance of understanding these dynamics of governance relates to their creation of structural constraints and opportunities in which your organizational design must function.

A good corporate governance framework encompasses not only staying out of scandals, which is very relevant. Decisions would be made, and it would ensure that management aligns their strategies towards long-term value creation instead of focusing on optimizing for shorter-term strategies.

Enterprise governance from the perspective of the CFO must navigate: The CFO typically plays a strategic role in linking these two areas to ensure business structures do not work counter to business goals, but instead serve to facilitate business success.

Attentive governance requires excellent preparation for board meetings, especially from the finance area. The financial officers have to convey strategic information to the boards from complex data.

Now, here's what most business books won't tell you: getting this triangle right is where many growing companies stumble. The informal structures that work fine at $10 million in revenue can create serious problems at $100 million.

If your board meetings feel more like family dinners than strategic discussions, or if major decisions happen in hallway conversations rather than formal processes, it might be time for a governance upgrade.

The larger the company grows, the more important it is for the governance structure to align with operational complexity.

When companies grow in size, the ‘trusting-the-gut-instinct’ kind of decision-making processes performed by startups act as bottlenecks.

In general, larger organizations require defined escalation processes and structures of authority from the governance triangle to operational staff.

A lack of such alignment would result in things such as boards micromanaging operational decisions while failing to identify strategic risks or executives making big decisions without adequate oversight.

That’s exactly why scaling companies invest so heavily in their governance structures to be able to deal with high volumes of transactions, complexity from regulations, and management of all stakeholders even before they ‘need’ it. The framework should be out in front of the ‘growth curve.’

And it’s exactly these types of changes that seasoned fractional CFOs can guide organizations through—that brings all the benefits of large-scale governance structures to organizations without committing to large-scale staff. Whether it’s to provide insight into strategic transactions or to set up sound financial reporting structures, it’s analyst-level talent in finance positions like these that make sound governance structures from burdensome to live up to.

The corporate form is not neutral; it instead drives what your firm can do and what it cannot. The wrong corporate form can not only hold you back but also restrict what your firm can do.

Decision speed, in particular, is the clearest direct effect. Flat structures allow for quick switching and market reaction; hierarchical structures allow for thoughtful consideration and strategic planning.

The trick here is to align organizational structures with strategic agendas. While startups have to have flat structures to be agile and prioritize speed over consensus, other industries need to have structured decision paths to ensure regulatory requirements are met.

Patterns of innovation differ vastly by structure.

Functional structures allow for expertise to be developed but have issues related to innovation involving cross functional cooperation. The matrix structure allows for innovation but inhibits implementation. The divisional structure allows for innovation in particular market areas but fails to take advantage of interdivisional opportunities.

Accountability mechanisms change with structure as well. Clear hierarchies make it easy to assign responsibility but can discourage calculated risk-taking. Flat structures encourage ownership but can create confusion when things go wrong. The best structures create what management theorists call "psychological safety"—environments where people feel safe to make decisions, take calculated risks, and learn from failures.

Intelligent leaders understand that restructuring results not in failure but in success. Amazon restructured dozens of times in its journey from being an online bookstore to a global technological platform. Restructuring helped Amazon reconfigure its capabilities to succeed in new areas.

It is exactly here where financial planning and forecasting knowledge matter significantly. Analyzing structural changes in financial terms, from staff planning to efficiency measures, calls for complex modeling capabilities beyond what small companies have in-house.

Multi-entity structures add layers of complexity that can create tremendous strategic and financial advantages—when managed properly.

Holding Companies exist primarily to own shares in other companies rather than conducting operations directly. Berkshire Hathaway represents the classic example: it owns dozens of operating companies but maintains a lean corporate structure focused on capital allocation and strategic oversight. Holding companies enable portfolio diversification, tax optimization, and risk isolation while maintaining strategic control.

Parent Companies actively manage their subsidiaries while also conducting their own operations. Disney operates theme parks and media properties while owning multiple subsidiary brands and international operations. This structure works well for companies that want to maintain operational integration while creating distinct legal entities for specific markets or product lines.

Subsidiaries are separate legal entities owned by parent or holding companies. They can be wholly owned or partially owned, domestic or international, operating or dormant. The key advantage is liability protection—problems in one subsidiary generally don't affect other entities in the corporate family.

Let's be honest for a moment: most entrepreneurs and even experienced executives find multi-entity structures intimidating.

The legal complexity, tax implications, and reporting requirements can feel overwhelming.

But here's what seasoned CFOs know: these structures aren't just for Fortune 500 companies.

Mid-market businesses often benefit enormously from properly designed entity structures, especially when expanding internationally or preparing for eventual exit transactions.

The challenge is getting expert guidance without breaking the budget, which is exactly why virtual and fractional CFO services have become so valuable for growing companies that need enterprise-level expertise on a flexible basis.

Whether you're considering an M&A strategy or planning business exit strategies, having experienced financial leadership can make the difference between structures that create value and those that create confusion.

Even well-intentioned leaders make predictable mistakes when designing or modifying corporate structures. The good news is that most of these pitfalls are avoidable with proper planning and periodic review.

represents the most common and costly mistake. Companies often maintain structures that worked in previous stages of growth or market conditions without considering how strategic priorities have evolved.

creates the corporate equivalent of traffic gridlock. When multiple people believe they have authority over the same decisions, or when no one knows who should make specific types of decisions, paralysis sets in. Clear decision rights aren't just about efficiency—they're about accountability and strategic execution.

Often develop organically as companies grow and evolve. What starts as a simple functional organization gradually accumulates matrix relationships, dotted-line reporting, and informal authority structures that nobody fully understands.

Can occur when employees have knowledge of their reporting structures but not their actual duties and power. When job descriptions sound like attorneys wrote them, role overlaps, and performance goals cause confusion and inefficiency from all corners.

The answer isn't to have a perfect first design—that’s not possible in dynamic business environments.

Rather, effective organizations have processes of reviewing and adjusting embedded in their management systems. Organizational effectiveness talks must be part of quarterly business reviews. The process of strategic planning must assess if structures align with future goals annually.

Role-mapping exercises may expose structural issues even before they cause problems in operations. When critical roles, responsibilities, and decision rights can be systematically captured and checked from time to time, structural changes can be evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

The best way to understand corporate structure is to examine how successful companies organize themselves to achieve specific strategic objectives. Three companies stand out for their distinctive and effective structural approaches.

Illustrates how big tech companies can be agile and entrepreneurial inside a structured framework.

Grouping Google, YouTube, DeepMind, and other business ventures under Alphabet as separate business segments enabled management to hold these entities accountable while allowing them to pursue their strategies independently.

The distinct characteristics of each business division operate individually and have their own set of management goals and financial performance measures in common.

The brilliance of Alphabet’s business structure rests in its ability to strike perfect harmony between autonomy and integration. The companies operate independently to pursue new flagship innovations but receive financial and strategic backing from their parent firm. Alphabet’s business structure has enabled Google to be leader in search advertising as well as autonomous vehicles and AI.

Proves that centralized structures can drive innovation and market leadership when properly designed. Despite its massive scale, Apple maintains a functional organization where design, engineering, marketing, and operations report directly to senior leadership.

This structure enables the integrated product development that defines Apple's competitive advantage and ensures its branding remains smooth and consistent throughout its product offerings.

The key to Apple's success is exceptional leadership development and a clear strategic vision.

Without the distributed decision-making that divisional structures provide, functional organizations require strong leadership at every level and crystal-clear strategic priorities. Apple's structure works because every functional leader understands how their area contributes to overall product excellence and customer experience.

The final bigwig - Amazon- showcases how complex organizations can balance functional expertise with product focus.

Amazon combines functional centers of excellence in technology, operations, and customer service with product-focused business units for retail, cloud services, advertising, and entertainment. Employees often have dual reporting relationships that balance functional development with product accountability.

Amazon's structure enables both operational efficiency and market responsiveness. Functional expertise drives continuous improvement in core capabilities like logistics and technology, while product focus ensures customer-centric innovation and market adaptation. The matrix works because Amazon invests heavily in leadership development, communication systems, and performance management.

The lesson from these examples isn't to copy their structures, but to understand how structure serves strategy. Alphabet's structure supports a portfolio of innovation bets. Apple's structure enables integrated product development. Amazon's structure balances efficiency with customer focus. The right structure for your company depends on your strategic priorities, competitive environment, and leadership capabilities.

The biggest question you might be asking as your business scales isn't whether to add another department or how to expand your current team, but :

What should we do with our organizational structure?

As you outgrow a startup phase flat growth structure, there comes an inevitable inflection point where informal decision-making and ad-hoc processes start breaking down, requiring deliberate choices about hierarchy, accountability, and operational frameworks that can support sustained growth.

For growing companies that need strategic guidance without full-time executive overhead, fractional and interim CFO services provide access to experienced leadership for structural planning, governance design, and strategic implementation.

Whether navigating rapid growth, preparing for investor due diligence, or managing complex reorganizations, the right financial leadership makes structure a strategic advantage rather than an operational constraint.

Reach out to us today at McCracken Alliance

for a no-strings complimentary structure analysis, so we can identify optimization opportunities and you can build an organizational framework that actually supports your growth objectives rather than constraining them!

Corporate structure refers to the formal system that defines how a company is organized in terms of departments, authority relationships, ownership arrangements, and governance mechanisms. It encompasses both internal organizational design and external legal relationships.

Structure determines decision-making speed, accountability clarity, strategic alignment, and operational efficiency. It affects everything from innovation capability to regulatory compliance, customer experience to employee engagement. Good structure amplifies organizational strengths; poor structure creates costly inefficiencies.

Functional (organized by expertise), divisional (organized by products or markets), matrix (combining functional and product focus), and flat (minimizing management layers) represent the primary models. Each offers distinct advantages depending on company size, strategy, and market conditions.

Corporate structure relates to internal organization and operational relationships, while legal structure (LLC, C-corporation, partnership) refers to how the business is legally recognized for tax, liability, and regulatory purposes. Companies often combine multiple legal entities within a single corporate structure.

Absolutely. Successful companies regularly evolve their structures to match changing strategic priorities, market conditions, and organizational capabilities. Restructuring is a normal part of business growth and strategic adaptation, not a sign of failure.