About Us

Solutions

Explore what ownership interest means in business, how it’s calculated and why it’s essential for equity, profits, and control in any entity

Explore what ownership interest means in business, how it’s calculated and why it’s essential for equity, profits, and control in any entity

Knowing who owns what, how much, and with what restrictions is essential for every business.

Ownership interest represents the stake a person or entity holds in a business—whether that's a slice of a tech startup, a percentage of a real estate LLC, or shares in a Fortune 500 company.

Straightforward right?

Not entirely. The legal, financial, and structural implications of owning a piece of any business entity create ripple effects that touch everything from day-to-day decision making to long-term succession planning.

Understanding Ownership interest is not just about figuring out who owns what percentage of each business.

It's also about grasping the implications of that ownership.

So ask yourself :

How do those raw percentages transfer into real power, profit rights, and responsibilities?

Because honestly?

These interests can make or break business relationships and strategic decisions.

The financial implications alone—from how working capital flows through the business to dividend policies—can significantly impact how ownership stakes create actual value for stakeholders.

Read on to find out the lowdown on ownership interest and how you can ensure your company is doing it right.

At its core, ownership interest defines the stake a person or entity has in a business.

This stake can be expressed as

But ownership interest isn't just a numbers game. It determines three critical elements that shape how businesses operate.

First, profit rights establish how earnings and distributions flow to owners.

A 30% ownership interest typically means a 30% share of profits, though partnership agreements and operating agreements can modify these default allocations.

Understanding how these distributions impact cash flow becomes crucial for stakeholders evaluating the real economic value of their ownership positions, particularly when businesses struggle with working capital management and liquidity challenges.

Second, voting power often correlates with ownership percentage, giving larger stakeholders more influence over major business decisions.

Voting power is essential. It is the right to be a part of key decisions such as key initiatives, merger agreements, and operational policies.

Recently, Jerry Greenfield from Ben and Jerry's departed after conflicts with parent company Unilever over the brand's independence and ability to speak out on social issues, particularly regarding Gaza.

The reason he left comes down to independence—he was supposed to have autonomy to pursue the company's social mission under the 2000 merger agreement, but felt that Unilever had silenced and sidelined the brand

This governance structure directly affects strategic initiatives, from where companies allocate capital for growth to operational policy changes that impact day-to-day business performance.

Third, asset distribution rights come into play during liquidation events, determining how proceeds are allocated when a business winds down or sells.

Nobody wants to think about liquidation or something like a leveraged buyout when it comes to their own company, but being protected legally with ownership during these events is essential.

Asset Distribution rights are essential when evaluating business worth and understanding how different ownership classes might receive different treatment during exit events.

The interplay between these rights creates the foundation for business governance and financial planning. When founders split equity or investors inject capital, they're not just dividing ownership—they're establishing a framework that will govern business relationships for years to come.

Different types of ownership interests serve distinct purposes and carry unique rights and obligations. Understanding these variations helps business leaders structure deals that align with strategic objectives and investor expectations.

This type of interest represents the most comprehensive form of ownership, combining rights to current assets with future profits (and some degree of voting power).

Typically, this is what most people envision when they think of being able to “own” part of a business - whether through common stock in a corporation or membership units in an LLC.

Usually, the financial reporting of equity ownership shows up directly on a company’s balance sheet under shareholders' equity. This represents the true net worth of the ownership stake in the business.

This offers a more targeted approach to ownership. As an owner, you are granted rights over future earnings without any immediate claim on any existing assets.

This structure works best and is great when incentivizing key employees and service providers who can contribute with sweat equity rather than capital. For example, in a startup, often times offering key players some incentive over future profits if their efforts help make the company successful

The upside here is that there's no dilution of existing owners' claims on current value. These arrangements often tie closely to business forecasting since the value depends entirely on future business performance.

Capital interest mainly focuses on asset rights. It often pops up in preferred equity structures wherein certain investors receive priority claims on company assets during liquidation events.

These arrangements are able to balance risk and reward by protecting the downside exposure while still allowing participation in business success.

How a business is structured from a legal standpoint fundamentally shapes how ownership interests operate, which creates distinct frameworks that affect everything from tax treatment to transfer restrictions.

Corporations, partnerships, and LLCs each handle ownership differently, and these differences matter enormously for strategic planning and operational decisions.

It centers around shares of stock, which, of course, represent proportional interests in the company's assets and earnings.

Shareholders have the ability to elect directors, who oversee managers, which creates a clear hierarchy and corporate structure that separates owners from day-to-day operations.

State corporate laws provide standardized frameworks for shareholder rights, making this structure predictable and well-understood by investors and advisors.

The financial reporting requirements for corporations demand consistent financial reporting practices that help stakeholders understand how ownership changes affect company performance and value.

Partnerships operate under a bit more flexible framework where partners can have vastly different rights and obligations within a company, regardless of their ownership percentages.

For example, a general partner might own 10% of the partnership but still maintain a full management authority, while a limited partner with 40% ownership might have no say in operations.

There are also Subsidiary relationships, which create another layer of complexity where a parent company holds a controlling interest in separate legal entities.

This allows for strategic reorganization of different business lines while also maintaining distinct liability protection and operational independence.

The tax implications of partnership structures often require sophisticated planning around revenue recognition timing and how income allocation affects individual partners' tax obligations.

Combine elements of both corporate and partnership structures.

Members can enjoy limited liability protection similar to corporate shareholders while maintaining the operational flexibility and tax advantages associated with partnerships.

This type of hybrid structure becomes very important when it comes to members contributing to different types of assets and services other than cash, which require careful management of working capital.

If you're structuring ownership for a real estate investment, an LLC might offer optimal tax treatment and operational flexibility.

For a high-growth technology company seeking venture capital, a Delaware C-corporation provides the standardized structure that sophisticated investors expect and understand. The choice affects everything from financing options to how future investment rounds will be structured and priced.

The distinction between legal and beneficial ownership creates one of the most important—and often misunderstood—concepts in business ownership.

Legal ownership appears on official records and documents, identifying who holds title to assets or shares.

Beneficial ownership reveals who actually enjoys the economic benefits and exercises control, regardless of what paperwork shows.

Trust arrangements often place legal ownership with a trustee while beneficial ownership remains with the trust beneficiaries.

Corporate holding structures might show a parent company as the legal owner of subsidiaries while individual shareholders maintain beneficial ownership through their parent company stakes.

Nominee arrangements, common in international business, place legal ownership with local entities while beneficial ownership stays with foreign principals.

Understanding what subsidiaries are and how they work becomes crucial for identifying true beneficial ownership in complex corporate structures.

Beneficial ownership has gained significant attention in compliance and regulatory contexts.

What is beneficial ownership?

It's a legal requirement to outline and name who has the actual ownership, control, and benefit from a company or legal entity.

Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements increasingly focus on identifying beneficial owners rather than just legal titleholders, particularly for businesses with complex ownership structures.

The Corporate Transparency Act and similar regulations require disclosure of beneficial ownership information to prevent money laundering and other financial crimes.

These compliance requirements often intersect with robust internal controls as companies implement systems to track and report ownership information accurately.

It's important for business leaders to understand this distinction as it helps in structuring transactions and relationships effectively.

Ownership percentage rarely translates directly into proportional control, creating a complex dynamic that shapes how business decisions actually get made. While a 51% owner might appear to have absolute control, operating agreements, shareholder agreements, and governance structures can modify or limit that authority in significant ways.

They typically correlate with ownership interests, but not always on a one-to-one basis.

Super-majority requirements for major decisions can give minority shareholders effective veto power over strategic initiatives. The more split up, the more complicated the voting rights.

Understanding these dynamics becomes crucial when developing better M&A strategies since control structures significantly impact deal negotiations and valuations.

Add another layer of complexity to control dynamics.

Some agreements require minimum ownership representation for valid decision-making, potentially allowing strategic shareholders to block actions by simply not participating in votes.

So those who want to block can say ‘nope, not today’ to initiates that they don't like.

These structures become particularly important during ownership transitions or when shareholders have conflicting interests about growth strategies—whether pursuing organic expansion or considering acquisitions.

Create additional control mechanisms that can override individual shareholder preferences during exit events.

So, as you can see, minority shareholders still have power in numbers even against majority shareholders in some circumstances.

These rights become particularly important when business owners are creating exit strategies and ensuring all stakeholders understand their options and obligations during potential exit scenarios.

Determining ownership percentages involves straightforward math in simple scenarios but can become complex as businesses evolve through multiple investment rounds, equity grants, and ownership transfers.

The basic formula provides a starting point:

Ownership % = (Your Investment ÷ Total Investment) × 100

However, this calculation assumes all contributions are equal in nature and timing, which rarely reflects business reality.

Cash investments, contributed assets, sweat equity, and assumed liabilities all factor into ownership determinations, often requiring professional valuation to establish fair exchange ratios.

The complexity increases when considering capital expenditures versus operating contributions, as different types of investments may warrant different ownership treatment.

Dilution events complicate ownership calculations as new investors or equity recipients join the business.

Each new share issuance reduces existing owners' percentages unless they participate proportionally in the new investment.

Understanding dilution mechanics helps business leaders anticipate how future fundraising or equity compensation will affect their ownership stakes.

This becomes particularly important when founders are preparing for fundraising and understanding how each funding round will impact existing stakeholder positions.

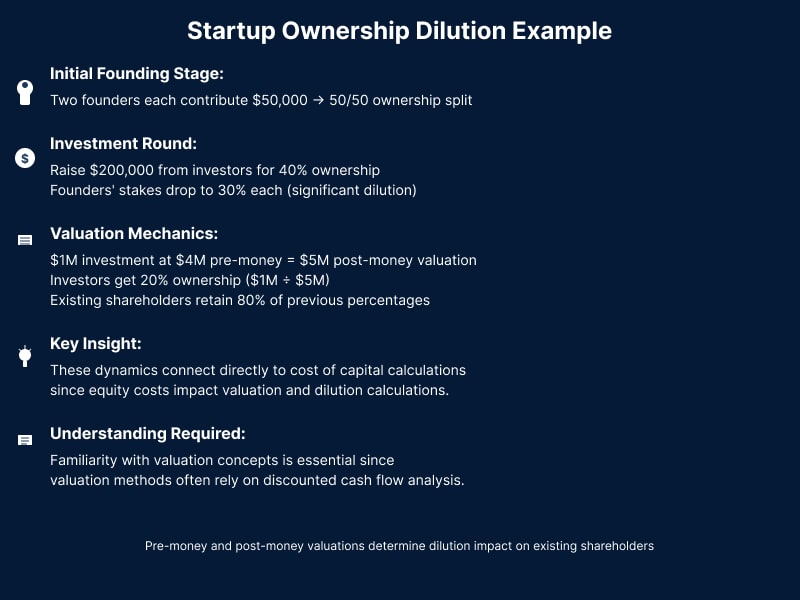

Consider a startup scenario where two founders initially split ownership 50/50 after each contributing $50,000.

When they raise $200,000 from investors in exchange for 40% ownership, the founders' stakes drop to 30% each—a significant dilution that reflects the value created between founding and investment.

These dynamics connect directly to cost of capital calculations since the cost of equity capital directly impacts valuation and dilution calculations.

Pre-money and post-money valuations determine how dilution affects existing shareholders during investment rounds.

A $1 million investment at a $4 million pre-money valuation creates a $5 million post-money valuation, giving investors 20% ownership ($1M ÷ $5M).

Existing shareholders retain 80% of their previous percentages (80% of 100% = 80% total). Understanding these mechanics requires familiarity with valuation concepts since valuation methods often rely on discounted cash flow analysis.

Cap table management provides detailed guidance on tracking these changes over time, particularly as businesses navigate multiple funding rounds and equity events.

Let’s look at some realistic business scenarios in which we can see how theoretical principles play out. These scenarios demonstrate how ownership structures affect real-world decision-making and financial outcomes.

Two co-founders launch a technology company together.

Founder 1 contributes $100,000 and agrees to serve as CEO

Founder 2 contributes $ 50,000 plus some proprietary technology that is valued at $50,000 and will also be serving as CTO.

Rather than splitting ownership 50/50, they allocate 55% to Founder 1 and 45% to Founder 2, reflecting the higher cash contribution and CEO role.

Still pretty close ownership split, but a bit of a caveat there, which makes things more equitable.

They then implement vesting schedules that require four years of continued involvement to earn full ownership, which protects the business if either founder decides to leave early.

This is like a partial “marriage’ commitment to the business, which protects it if either decides to “divorce”. This structure requires careful attention to deferred revenue accounting since the technology contribution may be recognized over time rather than immediately.

This ensures that as the business grows, and in years down the line each owner can look back and ensure they have been provided their fair share of the company.

That same startup later raised $500,000 from angel investors at a $2 million pre-money valuation.

The post-money valuation becomes $2.5 million, giving investors 20% ownership ($500K ÷ $2.5M).

Founder 1’s stake drops 55% to 44% (55% × 80%)

Founder 2’s goes from 45% to 36% (45% × 80%).

Both founders maintain their relative positions but accept dilution in exchange for capital to grow the business.

The investment terms often include provisions around different stock classes since investors typically receive preferred shares with enhanced rights and protections.

Each founder still has relatively high control over business operations, but needs to share ownership with others now due to their investment.

Let’s say three partners get together and form an LLC so they can purchase and renovate a rental property.

This structure reflects different risk tolerances and contribution types while ensuring fair economic allocation.

The ongoing financial management requires understanding how to optimize accounts receivable since rental income collection and tenant management directly impact cash distributions to partners.

These examples illustrate how ownership percentages represent starting points for more complex arrangements that address specific business needs and stakeholder objectives.

The key lies in creating structures that align economic incentives with operational responsibilities and risk tolerance.

Often, these arrangements benefit from professional guidance through fractional CFO services for fundraising or determining when startups should bring in fractional CFO support that provides objective analysis and strategic recommendations.

Decisions surrounding ownership interest create lasting consequences that extend far beyond initial equity splits or even investment terms.

Whether you're focused on dividing founder equity, bringing new investors in, or planning succession strategies, these choices have the power to shape business relationships and financial outcomes for years to come.

The most successful ownership structure of all balances current needs and future flexibility, creating business frameworks that can breathe and adapt as they evolve and as stakeholder interests change.

This requires understanding not just the legal and financial mechanics of ownership, but also its practical implications that impact decision-making, control, and long-term wealth creation.

Modern businesses also need to consider how financial controls and reporting systems will track and manage these ownership interests over time.

Smart business leaders recognize when ownership decisions require professional guidance. Complex equity structures, multi-party negotiations, and succession planning often benefit from experienced advisors who understand both the technical requirements and practical implications of different ownership arrangements.

Whether you need help with cash flow management, budgeting and forecasting, or strategic planning, having the right financial expertise can make the difference between structures that support your goals and ones that create unexpected constraints.

Mapping out ownership stakes for investors or partners?

McCracken’s CFO network can help founders model cap tables, ownership structures, and equity strategies with clarity.

Book a strategy session to explore how professional guidance can help you structure ownership interests that align with your business objectives and create lasting value for all stakeholders.

Ownership interest refers to the percentage or share of a business or asset that someone legally owns, giving them rights to profits, voting power, and asset distribution.

Ownership interest is typically calculated based on the proportion of capital contributed, number of shares owned, or agreed-upon equity stake: Ownership % = (Your Investment ÷ Total Investment) × 100.

Common types include equity interest (comprehensive ownership rights), capital interest (asset claims), profits interest (future earnings rights), and membership interest in LLCs (combined management and financial rights).

Yes, ownership can be sold, gifted, inherited, or transferred according to governing documents, buy-sell agreements, and applicable laws, though transfer restrictions often apply.

Legal ownership appears in official records and documents, while beneficial ownership refers to who actually enjoys the economic benefits and exercises control over the asset or business interest.